Revishun Revisoin Revision

Written by Aidan, a long standing maths teacher at one of the UK’s best schools. Aidan is available for private tutoring.

With end-of-year exams looming, what strategies can help ensure that you really present your very best under exam conditions?

There’s no denying that exams are stressful, but in most education systems they are a challenge that students have no choice but to grapple with. Most people understand that it’s better to start revision as early as possible – but without good revision strategies, it doesn’t matter when you start: inefficient revision won’t help you get what you want.

Revising different subjects requires different skills. The following tips are based on revising mathematics – although you could certainly apply them to other disciplines.

Revision: the big picture

It might come naturally to some students, but understanding the stages of revision is important if you’re going to revise effectively.

Common mistakes when revising are to focus on the wrong things – i.e. to practice skills that you can already do – and to over-rely on mixed practice when you should have formed specific goals.

Learn how to use your resources.

Revision resources basically fall into two main categories: topic-centred revision and mixed revision. Textbooks are usually great for topic-centred revision, where you can focus on questions of increasing difficulty on a single section of the syllabus, for example differentiation, or sequences. Old exam papers are a good example of mixed revision: you have work out what each question is asking you to do, which area of the syllabus it refers to and what techniques to apply. To revise effectively, you need to learn how to balance the two resources, and when to use each.

The diagnostic phase: start with a mixed resource.

When you are ready to begin your revision, starting with an old exam paper (or a specimen paper) is a good idea. Start by tackling it under exam conditions – with the right amount of time, and no access to notes. Then, when time is up, change to a different colour pen and keep going until you think you have done absolutely everything on the paper that you can – using your notes if you need to. Only when you have done absolutely everything you can, should you turn to the mark scheme. Go through each question – really critically – keeping track of which marks you gained under exam conditions and which marks you only got once time had run out or by using your notes. Ideally, get a teacher or tutor to do this section for you – experts are much better at critiquing work than novices, especially in the early stages of revision.

What’s the point of this? The key detail is that it highlights for you which topics you have strength in already, and which topics you need to focus your revision on. Once you have marked the paper, identify (again, with assistance if needed) all the topics in which you performed poorly, and rank them in terms of overall difficulty: some bits of your course will be conceptually more complex than others. You want to start by working on the easy ones.

The improvement phase: get stuck in.

It is better for you to build solid knowledge in a few topics than to have shaky knowledge of the whole course. When you have completed your first practice paper, look at the topics where you made mistakes, or didn’t know where to start, and pick the easiest three. Now turn to a topic-based resource, such as a textbook, and find the appropriate section. Most textbook exercises are structured from easy to hard – if you find the first few questions easy, skip ahead to tougher material. The important thing is to keep going until you find questions that you can’t do. This is the part that people typically shy away from, but it’s really the area where you’ll make the greatest gains. If you struggle to find the right resource, seek expert guidance.

When you find a challenging question, always spend a few minutes trying to work out what to do before seeking help. Write down anything that you can think of that’s relevant and see if you can work to an answer, even if you’re not confident. If you can’t even begin, then re-reading the examples in the textbook may help. Spend a bit of time on the question on your own, but if you really can’t make progress then remember that sometimes a friend, teacher, or tutor might be able to explain it to you in a way that really makes sense to you.

The reassessment phase: checking progress.

Only when you think you’ve done enough questions in a few topics to really say that you have improved is it worth going back to do some more mixed exam practice. Remember – an exam paper is basically a diagnostic tool which will help you determine your areas of weakness, so if you haven’t taken steps to improve, doing another paper won’t help you – you’ll just receive the same diagnosis.

You should start by going back to the questions that you got wrong on the last exam you did. Get a fresh copy of the paper and tackle the same question again. I have a mantra which I repeat for my students:

“If you can’t do now, under exam conditions, something which you have actually seen before:

how on Earth do you expect to be able to do something you haven’t seen before?”

You only really know you are on top of a subject when you are actually getting the questions right – so persevere with familiar material that you are finding tricky before tackling unseen questions.

Being comfortable with failure is good. But don’t practice failure.

It’s OK to make mistakes and if you aren’t getting anything wrong then you’re probably practicing questions which are too easy. In this sense, it’s important to embrace failure as part of the learning process. But many students make a big mistake with practice papers by doing too many of them too close together.

You should only start doing lots of practice papers when you’ve reached the exam standard you’re trying to attain and wish to improve your exam technique. Instead, what you are doing is practicing failure: unless you take the time to learn from your mistakes, each new practice paper that you study is likely to be at the same sort of standard as your last; you may make small gains, or one paper might be slightly better than the last because it happens to play to your strengths, but you won’t improve. Some students kid themselves into thinking that getting 60% on a lot of different papers somehow means that they will have covered a lot of the course and that therefore they’ll be able to perform better than that in the final exam. The truth is quite different, however: it’s probably just the same skills that they’ve been successful at each time. Furthermore, exam pressure is likely to make them perform worse on the day, not better.

Manage your time.

When you are doing timed exam practice, be really aware of the amount of time you have available for each mark on the exam, and stick to that allocation religiously. One of the biggest causes of under performance in exams is poor time management. Remember: your goal in the exam is to demonstrate the very best you can do in the time available. Perhaps you won’t get every question right – most people don’t. So at least make sure that you get every mark you deserve.

Most exams require you to get about one mark per minute to get full marks. So, suppose you have a 4 mark question to solve and it’s on a topic you think you can do. You get stuck in and things seem to be going well to begin with, but after a while you realise that things are going wrong and you still haven’t got the answer. Four minutes has passed. What do you do?

You might want to try again – after all, this is a question you thought you could do. But the truth is that you probably don’t really know why the question has gone wrong. If you did, you’d have fixed it already. Perhaps you’ve made a small mistake and your answer is mostly correct. In which case, you might have already picked up three out of four marks. Starting again might mean spending another four minutes on the question – which would be worth (at best) only one mark more than you already have. In contrast, you could use that time to tackle another question on the exam – where you might even earn full marks.

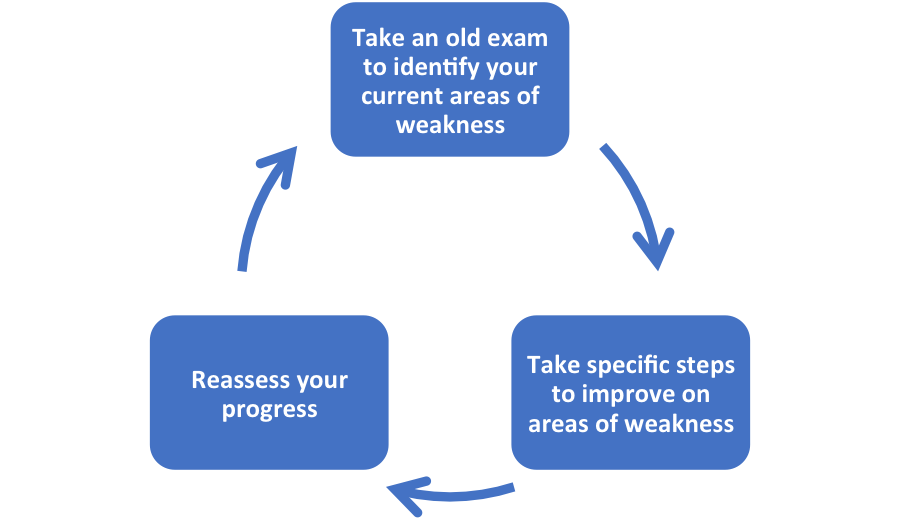

Learn the cycle and stick to it.

Overall, the pattern is simple:

- Do some mixed practice as a diagnostic tool

- Undertake specific steps to address areas of weakness

- Reassess and repeat

But it’s easy to stray: “I’ll just do another timed paper” (Do you need diagnosis? Or do you need to treat your weaknesses?); “I’ve finished revising chapter 3 so now I’ll look at chapter 4” (Is chapter 4 an area of weakness? Have you checked that you have really mastered the chapter 3 content?); “If I do enough practice papers, I’ll have seen all the topics” (Seeing topics isn’t enough – you need to do the questions successfully for yourself at least once).

Instead, if you make sure that you understand which phase you are in every time you sit down to revise, you’ll be able to make efficient and effective progress towards a top exam grade. Good luck!

Warp Drive Tutors, Inc. has been developed independently from and is not endorsed by the International Baccalaureate Organization. International Baccalaureate®, Baccalaureat International®, Bachillerato Internacional® and IB® are registered trademarks owned by the International Baccalaureate Organization.