Written by Giuseppe; Giuseppe is available for private tutoring.

Conservation of Linear Momentum

Almost everybody can easily stop a ball thrown at 40 km/h in a tenth of a second but nobody can do the same with a car travelling at 40 km/h.

It’s the product of mass and change in velocity that really matters when it comes to evaluating the forces exerted on a body, in order to change its motion.

Definition of momentum

It is convenient to define a physical quantity called momentum, usually indicated by the symbol ![]() , as the product of its mass

, as the product of its mass ![]() by its velocity

by its velocity ![]()

![]()

The momentum is a vector quantity which has the same direction as the velocity of a body.

The unit of measurement of momentum in the SI system is the product of the units of mass and velocity and thus is kg m/s.

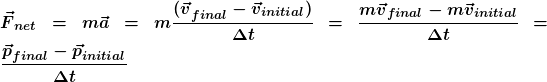

A new Form of Newton’s Second Law

Newton’s Second Law can be expressed in terms of change in momentum:

which can be written in the more compact form

![]()

It’s interesting to notice that this is actually the way in which Newton wrote his second law in his original work Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Latin for “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy”).

Since we can write this equation as ![]() (a simple idea which, as we will see later, has very interesting consequences), the SI units of momentum should be equivalent to the product of the units of force and time and this is indeed the case as kg m/s = N s.

(a simple idea which, as we will see later, has very interesting consequences), the SI units of momentum should be equivalent to the product of the units of force and time and this is indeed the case as kg m/s = N s.

Example 1

If a constant net force of 130 N acts for 10 ms on a 50 g ball initially at rest, what will its final momentum be?

Since the ball is initially at rest, its initial momentum is zero: ![]() . From the expression of Newton’s Second Law we get

. From the expression of Newton’s Second Law we get

![]()

The final momentum will have thus the same direction as the force acting on the body and magnitude

![]()

The impulse of a force and its graphical interpretation

In the expression

![]()

the net force on the left-hand side is the average force acting during the time ![]() . We can give a precise meaning to this average force by introducing another physical quantity named the impulse.

. We can give a precise meaning to this average force by introducing another physical quantity named the impulse.

The impulse ![]() of a constant force

of a constant force ![]() acting for a time

acting for a time ![]() is given by

is given by

The impulse is a vector quantity. For a constant force, its direction is the same as the direction of the force. The SI unit of impulse is N s.

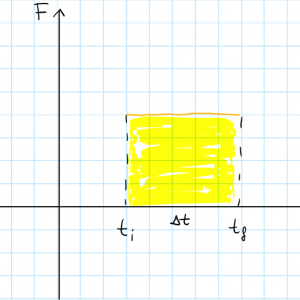

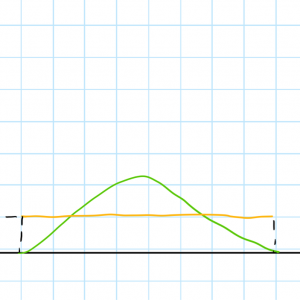

If we plot the intensity of the force versus time, for a constant force the graph will look like the one below:

The magnitude of the impulse is represented by the area highlighted in yellow.

We can represent the magnitude of the variable force on a plot as below:

The impulse delivered by the variable force has the same direction of the force and, like in the case of a constant force, has intensity equal to the area below the graph of the intensity of the force vs the t axis.

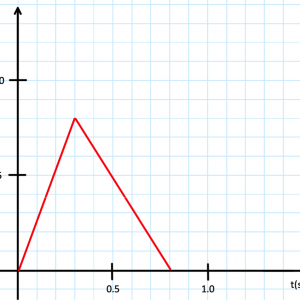

The magnitude of a force of constant direction varies with time according to the plot below. What is the impulse of the force?

The impulse and the force have the same direction. To know the magnitude of the impulse, we need to calculate the area of the triangle. The base is 0.8 s while the height is 8.0 N. So the magnitude of the impulse is given by

![]()

Average force

The definition of impulse of a variable force allows us to give a precise definition of average force.

If a variable force ![]() acts for a time

acts for a time ![]() , its average value

, its average value ![]() is the value of a constant force that delivers the same impulse

is the value of a constant force that delivers the same impulse ![]() as the force

as the force ![]() in the same time

in the same time ![]() :

:

![]()

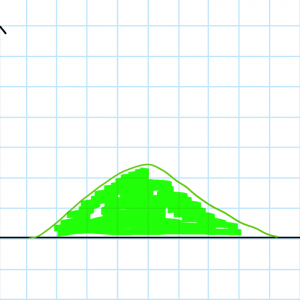

For a variable force of constant direction, the average value of the magnitude is such that, in a force versus time plot like the one below, the area below the green line equals the area below the yellow line:

Impulse and momentum change

Newton’s Second Law in the form ![]() can be easily rewritten as

can be easily rewritten as

![]()

Since the ![]() on the left-hand side is actually the average force, the whole left-hand side is the impulse of the net force. Hence, we can write that the impulse of the net force acting on a body is equal to its change in momentum:

on the left-hand side is actually the average force, the whole left-hand side is the impulse of the net force. Hence, we can write that the impulse of the net force acting on a body is equal to its change in momentum:

![]()

Example 3

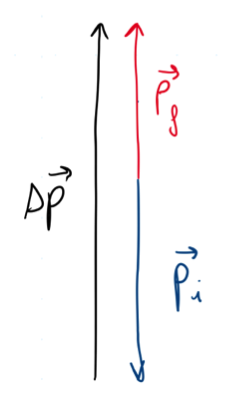

A 50 g tennis ball is falling vertically to the ground. Immediately before hitting the ground its speed is 15 m/s. Immediately after the bounce its speed is 11 m/s. The ground contact time is 10 ms. What is the average normal force exerted by the ground on the ball?

Let’s start by calculating the impulse of the net force, which is easily obtained in terms of the change in momentum.

![]()

![]()

The average net force during contact is also directed upwards and its magnitude is given by the magnitude of the impulse divided by the contact time

![]()

During contact two forces act on the ball: the weight ![]() and the normal force

and the normal force ![]() exerted by the ground. The net force is just the vector sum of these two. Since the weight is constant, its average is just its value:

exerted by the ground. The net force is just the vector sum of these two. Since the weight is constant, its average is just its value:

![]()

![]()

Since the net force is directed upwards and the weight force downwards, the magnitude of their difference is the sum of their magnitudes. Considering the average values, we have

![]()

Momentum of a system

In the example we have just discussed, the weight force is much less than the contact force between the ball and the ground. This is very common in case of rebounds, collisions or explosions: the contact force between the bodies involved are much larger than any other force involved.

When a system is composed of several bodies, the total momentum of the system ![]() is simply the sum of the momenta of the bodies the system is made up of:

is simply the sum of the momenta of the bodies the system is made up of:

![]()

Internal and external forces

We can distinguish the forces acting on each body of the system in two categories: internal and external. Internal forces are exerted by other bodies of the same system, while external forces are exerted by bodies which are not part of the system.

There is a very important result regarding internal forces.

The vector sum of all the internal forces acting in a system is null.

This is a direct consequence of Newton’s third law.

Let’s consider two bodies A and B inside our system. Newton’s third law states that if there is a force ![]() that A exerts on B, then there is also a force

that A exerts on B, then there is also a force ![]() that B exerts on A and

that B exerts on A and ![]() .

.

Thus if we add all internal forces, we need to put into the sum both ![]() and

and ![]() . Since they are opposite, their sum is

. Since they are opposite, their sum is

![]()

This is true for any force exerted by a body of the system on any other body of the same system and thus the internal forces always come in couples whose sum is null. Hence, the sum of all internal forces in null.

Conservation of momentum

Let’s now consider the change in total momentum ![]() in a time interval

in a time interval ![]() during which both internal and external forces act on the bodies of the system. It will be equal to the sum of the momentum changes of each body:

during which both internal and external forces act on the bodies of the system. It will be equal to the sum of the momentum changes of each body:

![]()

The momentum of a body of the system will change due to the effect of both internal and external forces acting on it. If we call ![]() and

and ![]() respectively the sum of all internal and all external forces, we get

respectively the sum of all internal and all external forces, we get

![]()

Since we have already proven that the sum of all internal forces is zero, ![]() , we get

, we get

![]()

From this analysis we can deduce a very important result, known as the law of conservation of momentum.

If the sum of all external forces acting on a system is null, then its total momentum doesn’t change:

![]()

Collisions and explosions

In a collision or an explosion, the forces acting on the bodies involved are much larger than the external forces. Often, the sum of all external forces is zero but even when it is not so, they are so much weaker than the internal forces that they can be neglected. In such situations, we can apply the law of conservation of momentum.

Example 4

A cart of mass ![]() is moving on a straight rail towards another cart of mass

is moving on a straight rail towards another cart of mass ![]() which is initially at rest. The initial speed of the first cart is

which is initially at rest. The initial speed of the first cart is ![]() . After the collision, the two carts remain attached to each other. What will be the final speed of the two carts?

. After the collision, the two carts remain attached to each other. What will be the final speed of the two carts?

Let’s call ![]() the final speed of both carts. Applying the conservation of momentum we get

the final speed of both carts. Applying the conservation of momentum we get

![]()

Since ![]()

![]() we get

we get

![]()

Elastic, inelastic and explosive collisions

Collisions can be distinguished in three categories, according to what happens to the total kinetic energy of the bodies involved.

For a system composed of multiple bodies, the total kinetic energy is simply the sum of the kinetic energies of all its bodies. If a body of mass ![]() is point-like or doesn’t spin during its motion, and has speed

is point-like or doesn’t spin during its motion, and has speed ![]() , its kinetic energy is given by

, its kinetic energy is given by

![]()

The total kinetic energy of a system of bodies is thus given by

![]()

We can distinguish collisions in three categories

Elastic collisions: the total kinetic energy of the system doesn’t change

![]()

Inelastic collisions: the final total kinetic energy is less than the initial total kinetic energy

![]()

Explosive collisions: the final total kinetic energy is more than the initial total kinetic energy

![]()

All collisions of large bodies are basically inelastic but if the two bodies are rigid enough, the collision can be considered elastic: it is the case of two pool balls or two carts with good quality bumpers, for example.

Collisions between microscopic particles, like the atoms in a gas, are instead almost always perfectly elastic.

For an elastic collision of two bodies of mass ![]() , initial speeds

, initial speeds ![]() and final speeds

and final speeds ![]() we can write

we can write

![]()

In an inelastic collision, in agreement with the Law of Conservation of Energy, the decrease of kinetic energy is compensated by an increase of other forms of energy, usually thermal or acoustic energy (carried by sound waves) or even the deformation energy acquired when a body changes shape (also called elastic energy).

A collision in which at the end all bodies remain attached and moving with the same speed is called completely inelastic.

Explosive collisions involve instead some sort of release mechanism (like a spring or a chemical explosive) that unleashes some energy previously stored in other forms and transforms it into kinetic energy: a good example is given by fireworks, whose pieces blow up in fancy shapes with an increase in their total kinetic energy.

A classic application of the concepts of conservation of momentum and energy is the so-called ballistic pendulum, which is used to accurately determine the speed of a fast bullet. A bullet of mass

We can apply the conservation of momentum during the collision of the bullet and the wooden block. Let’s call ![]() the speed at which the block (with the bullet inside) moves immediately after the collision:

the speed at which the block (with the bullet inside) moves immediately after the collision:

![]()

Notice that the collision is inelastic and some of the kinetic energy of the bullet is used to deform the wooden block while some is converted into thermal energy.

After the collision, the mechanical energy of the system is conserved during the motion. When the block reaches its highest point, its speed is zero and thus all its kinetic energy is converted into gravitational potential energy:

![]()

Substituting into the previous equation we get

![]()

We have attempted to elucidate some concepts about momentum where students often encounter difficulty. Remember that as much as this information might prove helpful nothing will improve your understanding more than cranking through lots and lots of problems. The problems might seem confusing, but remember – if you are confused that does not mean you can’t do physics. It means you are engaged with, and wrestling with, the material. That is how you learn!